We have just wrapped up COP30, the Amazon COP, in Belém, Brazil. The setting couldn’t have been more symbolic: the humid heat of the rainforest, the broad expanse of the Guamá River, and the palpable urgency of a biome at its tipping point. The expectation was clear: this would be the moment the world finally operationalized the link between forest conservation and climate stability.

Yet, as the delegates fly home, we are left with a stark contradiction: the Belém Paradox.

While the summit launched new financial instruments and strengthened the recognition of Indigenous rights, the final binding text, the Global Mutirão, is conspicuously silent on the one commitment that matters most right now: a concrete, mandatory roadmap to halt deforestation.

Here is my assessment of what happened, what the data shows and where we go from here.

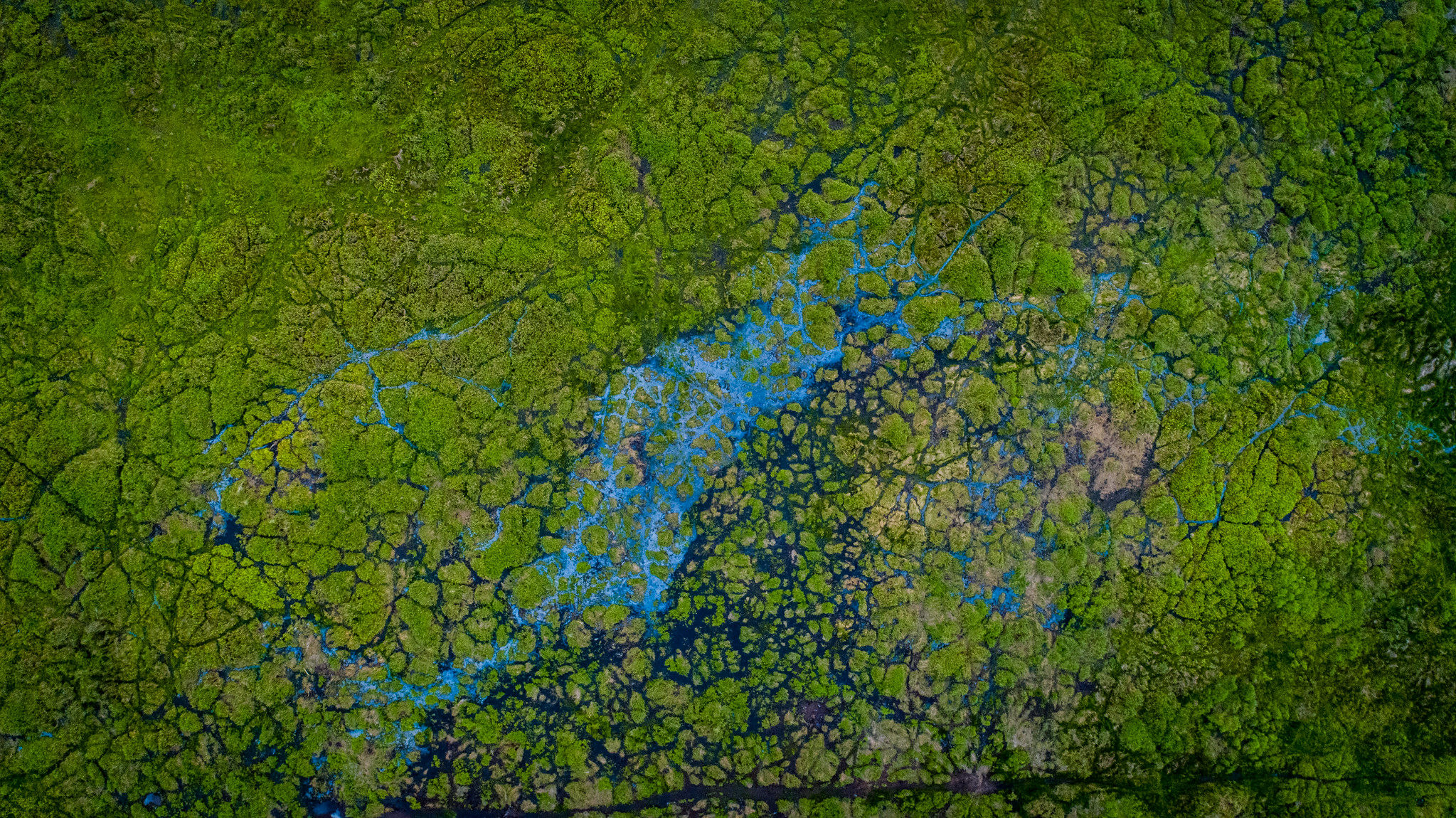

The COP30 venue in Belém, Brazil, where negotiations ended without a binding global commitment to halt deforestation. Photo by Climate Acceptance Studios

1. The “Mutirão” reality check: Diplomacy vs. biophysics

The Brazilian Presidency pushed hard for two ambitious roadmaps: one to phase out fossil fuels and one to halt deforestation. The strategy was to link them, acknowledging the obvious: we cannot save the Amazon if the world keeps warming.

This strategy backfired. In the final hours of negotiation, opposition from the Like-Minded Developing Countries and major petrostates led to the removal of the fossil fuel roadmap. In the diplomatic fallout, the linked deforestation roadmap was also taken out of the binding decision.

The result? The Global Mutirão focuses on adaptation and general cooperation but lacks the teeth of a binding commitment to stop forest loss. Instead, the roadmaps have been launched as voluntary initiatives – a coalition of the willing rather than a global mandate.

Key takeaway: The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process proved unable to digest the complexity of the forest–climate nexus. We have effectively moved from a consensus-based approach to a plurilateral one, where progress rests on voluntary clubs of nations rather than global law.

2. The data could not be clearer: The rules of the game have changed

While diplomats debated text, the biosphere told a different story. Data from 2024 and 2025 show that the drivers of deforestation are shifting in dangerous ways.

- We are 63 percent off track:To meet the 2030 goal of zero deforestation, steep annual declines were needed. Instead, 2024 rates remained far above the required trajectory.

- Fire is the new chainsaw: Historically, agriculture (soy, beef, etc.) was the main driver of forest loss. In 2024, for the first time in many regions, fire surpassed agricultural clearing as a driver of primary forest loss.

- The feedback loop:Climate-induced droughts are drying out rainforests, leaving them highly susceptible to fires that release immense quantities of CO₂, which drives more warming. This confirms Brazil’s central argument: we cannot fence off forests if temperatures continue to rise.

3. The silver lining: Finance and rights

If the political outcome disappointed, the financial and rights-based elements provide a measure of hope.

The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF)

This was Brazil’s major ask.

- The Good: The mechanism is innovative and officially launched. It pays nations for standing forests as an asset class, not just for avoided deforestation.

- The Bad: It secured USD 6.6 billion in initial pledges, a meaningful sum but far short of the USD 25 billion target needed to shift global incentives. The funding model carries risks, and implementation will be crucial.

Indigenous stewardship

The Belém Action Mechanism and the demarcation of new territories – including 14 in Brazil – mark a shift from viewing Indigenous Peoples as stakeholders to recognising them as primary implementation partners. With no binding global commitment to halt deforestation, secure Indigenous land tenure may now be the most effective climate policy available.

Micaela Fachin, an agroforestry producer from the Roya community in Peru, shows native forest species. Photo by Juan Carlos Huayllapuma / CIFOR-ICRAF

4. What comes next?

Belém showed that the geopolitical consensus for a binding deforestation phase-out does not exist. The era of relying on UN negotiations to “ban” deforestation is likely over.

The path forward rests on three pillars:

1. High-integrity carbon markets

WithArticle 6.4 operationalized, private capital must flow into forest restoration at an unprecedented scale. Yet the market remains stuck in a carbon-tunnel vision. Carbon sequestration matters, but forests provide more immediate benefits for water regulation, local temperature and biodiversity.

2. Making the TFFF work

Pledges must be deployed quickly to demonstrate that the model is viable and capable of attracting institutional capital to reach the USD 25 billion goal. A thorough review will be needed to address design flaws.

3. Tackling supply chains

With the UN process stalled, regulations such as the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) and emerging measures in China and the UK are becoming the de facto global rules governing forest-risk commodities.

The bottom line

COP30 was the Forest COP without a forest mandate. We have the diagnosis – the Global Stocktake – and the prescription – stop deforestation – but the patient refused the medicine. The effort to save the world’s forests now moves from negotiation halls to markets, courts and the territories where people defend them every day.