Wetlands┬Āinfluence climate,┬Āwater┬Āand biodiversity across much of the tropics and subtropics, yet many┬Āremain┬Āpoorly mapped.┬ĀTheir extent,┬Ācondition┬Āand seasonal┬Ābehaviour┬Āare often difficult to track, leaving countries with limited information as they plan for climate adaptation and mitigation. As governments prepare new commitments ahead of COP30, access to reliable spatial data has become increasingly important.┬ĀFirst developed and published by the┬ĀCenter for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF),┬Āthe┬ĀGlobal Wetlands datasets┬Āare now available on the UN Biodiversity Lab (UNBL), giving researchers,┬Āplanners┬Āand policymakers a clearer view of where these ecosystems are found and how they function.┬Ā

The UN Biodiversity Lab ŌĆö a free, open-source spatial data platform created by several UN agencies, including the Secretariat of the UN Biodiversity Convention,┬ĀUNDP┬Āand UNEP ŌĆö has now made the datasets accessible to users worldwide. Through the platform, anyone can visualize and download wetland information at national and subnational scales.┬ĀFondzeyuf┬ĀFolah, a data officer at UNEP-WCMC, announced the release on 8 November 2025,┬Ānoting that the UNBL aims to support country-led planning,┬Āmonitoring┬Āand reporting for both people and the planet. He added that the datasets will also be added to the┬ĀSpatio┬ĀTemporal Asset Catalog (STAC), making them even more discoverable.┬Ā

ŌĆ£The UNBL facilitates access to spatial datasets that can assist stakeholders in country-led efforts for planning, monitoring, and reporting to take action for people and┬Āplanet,ŌĆØ┬ĀFolah┬Āwrote.

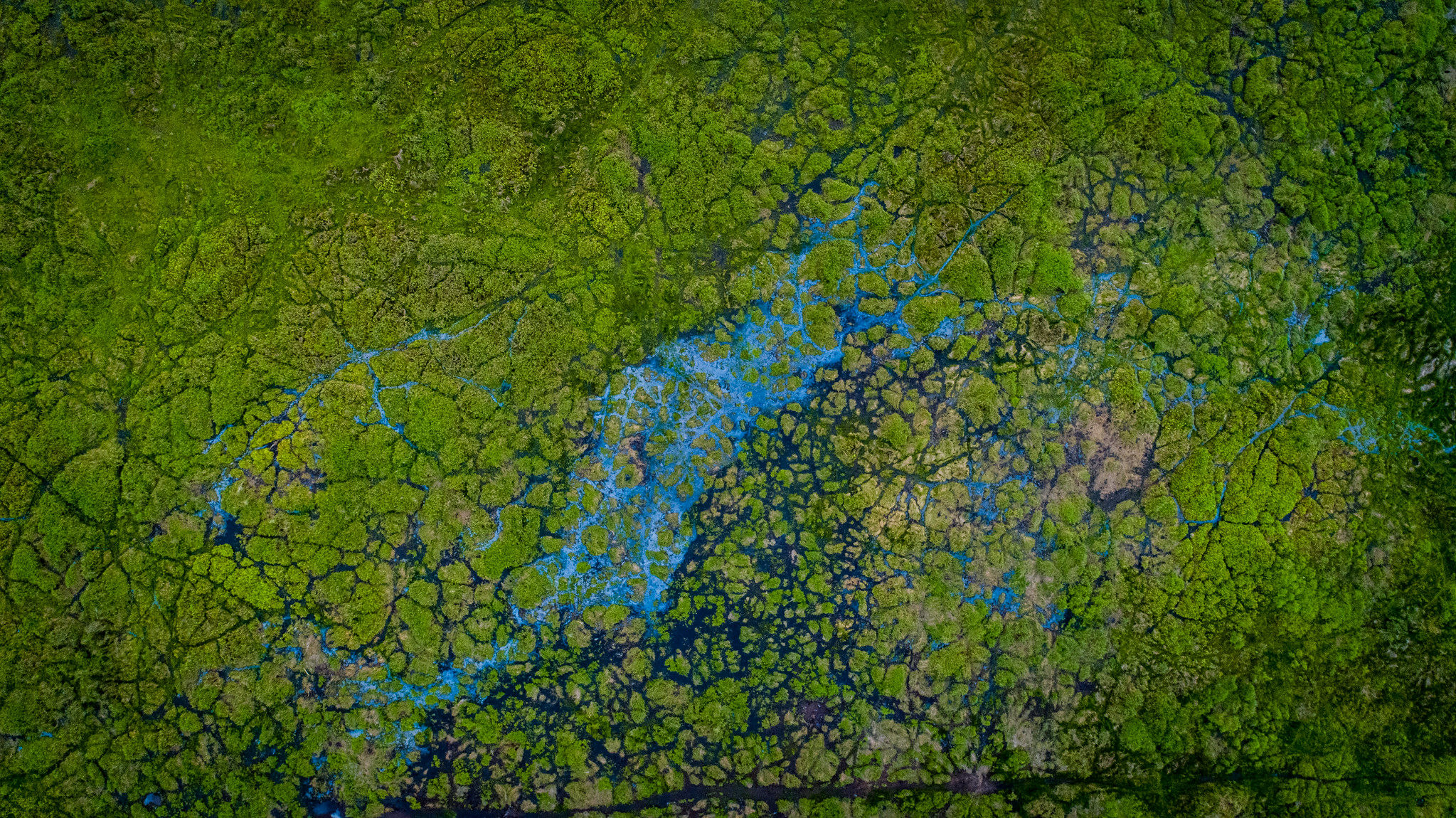

Peatland vegetation and waterways in the Padang SugihanŌĆōSebokor Wildlife Reserve near Rambutan, South Sumatra, Indonesia, a key habitat for wild elephants.

Photo by Faizal Abdul Aziz / CIFOR-ICRAF.

A milestone and contribution to global open science

┬ĀThe┬ĀGlobal Wetlands┬Āwork┬Ābegan┬Āthrough┬Āthe┬ĀSustainable Wetland Adaptation and Mitigation Program┬Ā(SWAMP),┬Āwhich set out to map tropical┬Āpeatlands and understand their distribution and condition.┬ĀYears of fieldwork, modelling,┬Āmapping and database development┬Āresulted┬Āin a highly┬Ācited┬Āscientific┬Āarticle in a respected┬Ājournal┬Āand a widely used interactive map┬Ādatabase.

ŌĆ£These resources are widely used, especially when visitors aim to locate degraded wetlands for restoration and intact wetlands for conservation in the context of climate change mitigation and adaptation,ŌĆØ said Daniel┬ĀMurdiyarso, CIFOR-ICRAF principal scientist. He noted that wetlands ŌĆö including peatlands and mangroves ŌĆö are among the worldŌĆÖs largest natural stores of carbon.┬Ā

Wetlands are natureŌĆÖs secret weapon against climate change, providing┬Āclean water, abundant food, natural flood barriers,┬Āand powerful carbon storage. Despite covering just┬Āsix┬Āpercent┬Āof the Earth, their services are valued at more than 7.5┬Āpercent of the worldŌĆÖs┬Āgross domestic product (GDP). Wetlands also┬Āsupport┬Ālivelihoods in farming, fishing,┬Āand tourism. Yet┬Āeach┬Āyear, we lose 0.52┬Āpercent┬Āof these vital ecosystems, making┬Āglobal┬Āefforts┬Āon┬Āclimate and biodiversity even┬Āmore difficult.┬Ā

ŌĆ£The fact that UNBL is interested┬Āin bringing┬Āthe database┬Āionto their platform signifies the importance┬Āof having such information┬Āto explore┬Āco-benefits, especially biodiversity conservation and┬Āenrichment beyond carbon,ŌĆØ┬ĀMurdiyarso┬Āadded. He┬Āalso emphasized┬Āthat┬ĀŌĆ£countries┬Āobliged to meet their┬ĀNationally Determined Contribution (NDC) targets will benefit from┬Āthe spatially explicit database to┬Āidentify where degraded wetlands are and what kind of intervention are needed,┬Āincluding efforts for┬Ārewetting or revegetating the area.ŌĆØ┬Ā

For┬ĀCIFOR ICRAFŌĆÖs┬ĀData┬Āand┬ĀInformation Services┬Āteam,┬Āthe publication marks┬Āan important step┬Āin advancing open science.┬ĀŌĆ£It marks a major milestone in┬Āadvancing open, science-based data for global sustainability,ŌĆØ┬Āsaid┬ĀSufiet┬ĀErlita, the teamŌĆÖs senior┬Āmanager. ŌĆ£Being hosted on┬Āa┬ĀUN-endorsed platform reflects international recognition of the CIFOR-ICRAFŌĆÖs data quality, transparency,┬Āand policy relevance,ŌĆØ she added with a glimpse of pride.┬ĀŌĆ£It┬Ādemonstrates┬Āhow the organizationŌĆÖs spatial research and geospatial innovation are trusted to inform evidence-based decision-making on biodiversity, climate,┬Āand land use worldwide.ŌĆØ┬Ā┬Ā

She underlined┬Āthat the recognition also┬Āreflects┬ĀCIFOR-ICRAFŌĆÖs commitment to open data principles, ensuring that high-quality spatial information is freely accessible and interoperable for governments, researchers,┬Āand practitioners worldwide. The┬Āpublication┬Āof the┬Āwetlands┬Ādataset strengthens┬Āglobal data sharing and┬Āopen science,┬Āshe added, and┬Āreinforces┬ĀCIFOR-ICRAFŌĆÖs visibility among┬Āpartners working on similar themes.┬Ā

Wetlands worldwide are under threat┬Ā

Wetlands are disappearing┬Āthree times faster than┬Āforests.┬ĀA new report┬Āby┬Āthe Ramsar Convention Secretariat,┬Āthe Global Wetland Outlook 2025: Valuing, conserving, restoring and financing wetlands (GWO 2025),┬Āestimates that┬Āat least 411 million hectares of the worldŌĆÖs wetlands have been lost since 1970.┬ĀThe report also┬Āwarns that without urgent action,┬Āanother┬Āfifth of the worldŌĆÖs remaining wetlands could┬Ādisappear┬Āby 2050, leading to an estimated USD39 trillion in┬Ālost┬Ābenefits that support people, economies,┬Āand nature.┬Ā┬Ā┬Ā

For example, in Indonesia, peatlands are often drained┬Āand cleared┬Āfor┬Āagriculture, especially oil palm cultivation. However, when these┬Āpeat soils dry,┬Āthey release┬Ālarge amounts┬Āof carbon into the┬Āatmosphere.┬Ā┬Ā

In the┬ĀAmazon,┬Ānutrient-rich floodplain wetlands attract agribusiness expansion, with companies seeking land for soy and rice farming.┬Ā

Across the Congo Basin, vast peatlands ŌĆö many still unmapped ŌĆö are increasingly threatened by logging, mining and other industrial activity. Similar pressures are emerging in many regions.

Riparian forests and wetlands along the Congo River near the Yangambi region in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Photo by Ahtziri Gonzalez / CIFOR-ICRAF.

ŌĆ£Wetlands are often seen as empty or useless land, mostly because they are difficult places to walk, study, or even visit,ŌĆØ said┬ĀCIFOR-ICRF scientist┬ĀArimatea┬Āde Carvalho Ximenes.ŌĆ£Their harsh and hidden environments mean that most people still do not understand how important they are. Wetlands protect communities from floods, clean our water, and are breeding grounds for fish, crabs, and many other species that support food and local economies.ŌĆØ┬Ā

He noted that wetlands have historically been poorly mapped, leaving them out of land-use plans and national policy discussions. ŌĆ£Because they are so hard to access, wetlands have been poorly mapped and rarely included in policy decisions. The Global Wetlands Map datasets help change that,ŌĆØ he added. ŌĆ£By combining the Global Wetlands Map with other information, such as deforestation or land-use change, decision makers can finally see where these valuable ecosystems are located, and where action is most needed.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£With this knowledge, we have a much stronger base to protect what remains, restore what has been damaged, and plan for a future where nature and people thrive together.ŌĆØ

The importance┬Āof wetlands┬Ādatasets┬Ā┬Ā

Sigit┬ĀDeni┬ĀSasmito, senior researcher at┬ĀTropWATER at┬ĀJames Cook University, Australia, also mentioned the importance of the datasets.┬Ā“They┬Āallow┬Āresearchers, planners, and wetland managers to assess┬Ācurrent wetland extent, monitor changes, and establish reliable baselines for management and restoration,” he said. “The datasets have already┬Ābeen used in Indonesia┬Āand other tropical countries to support peatland restoration planning, mangrove conservation, and national-scale land-use assessments.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Scientists┬Āwidely agree that protecting┬Āwetlands is┬Āone of the most effective natural strategies for climate mitigation.┬ĀIf┬Āstored carbon┬Āfrom peatlands and mangroves were released, it would significantly accelerate global warming.┬Ā

To direct conservation and restoration efforts, decision-makers need to know which wetlands to prioritize.┬ĀThe Global Wetlands┬ĀŌĆö together with the interactive map ŌĆö┬Ādatasets, featured with a visual interactive map, can help┬Āgovernments and organizations prioritize conservation and restoration investments. They┬Āalso┬Āsupport integrating┬Āwetland┬Āinformation┬Āinto biodiversity and climate planning tools, such as National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs), strengthening┬Āreporting on global biodiversity targets and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).┬Ā