The forest crisis is both a technological and a moral test. Solutions are finally within reach, but their success depends on one essential question: who leads?

For too long, the response has followed a familiar pattern. The narrative sung like a litany: “Global experts from the North come, help, design, fund, leave.” The climate crisis — and even more so the forest crisis — has often been treated as something to be solved elsewhere, designed elsewhere and funded elsewhere.

At the recent Orange forumin Jakarta, however, several statements struck a chord; a different tone emerged, expressed not through declarations but through pointed questions that cut to the heart of the matter.

Who benefits?

- “Top-down post-2nd world war grant architecture”;

- “Finance for good, but finance for whom?”;

- “Climate action for good, but climate action for whom?”;

Who leads?

- “We are only making the transition if we are not dictated by the taxonomy of the North”;

- “We need coherent policy answers from the Global South to counter-argue the Global North hegemony”;

What foundations?

- “Inclusion should not be an aspiration, but the foundation”;

- “Moving from counting women to valuing gender contribution to society and economy.”

These are not slogans. They expose a deep fault line in how we finance, govern and value nature-based solutions. If the actors closest to declining forests aren’t central in design, leadership and benefit, then we risk reproducing the extractive patterns we claim to disrupt.

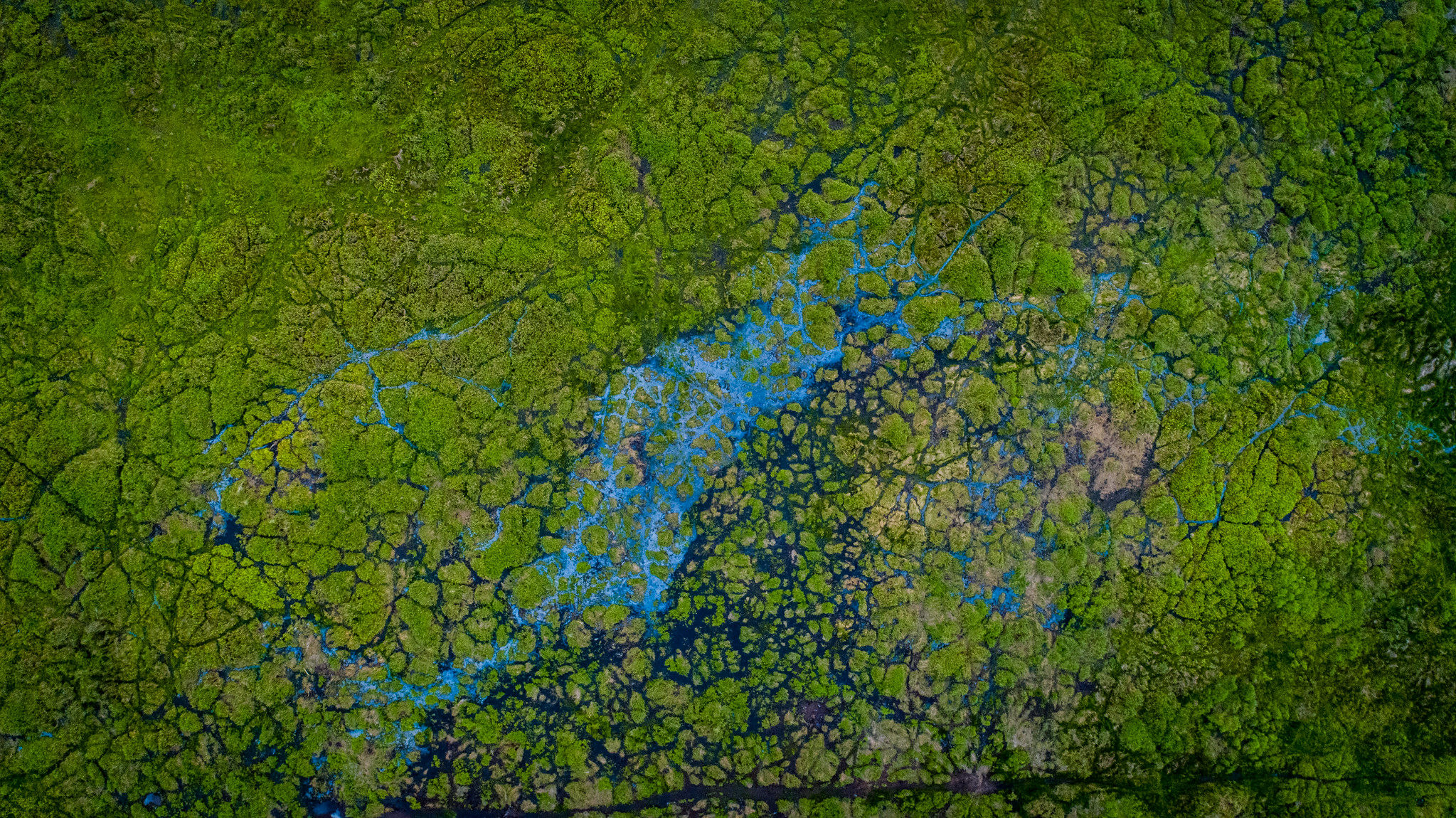

A community at the foothills of the Atewa forest range in Ghana, where forest landscapes and local livelihoods intersect with national decisions on forest protection and finance.

Photo by Ahtziri Gonzalez / CIFOR-ICRAF

A moral imperative with a financial counterpart

This moral urgency now has a financial counterpart. The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF), led by Brazil in partnership with forest-rich countries such as Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and with private/public capital, offers an architecture that departs from the top-down, donor-driven model. As Robert Nasi explains, the USD 4 per hectare figure often quoted in the media misses the point: this is not a payment to farmers, per se, but part of a sovereign‐level performance bond.

The mechanism

A blended-finance investment fund of about USD 125 billion aims to deliver a multi-billion-dollar annual payout to forest nations.

The incentive structure

The USD 4 per hectare is not intended to outbid the profit from clearing land for palm oil or soy. Instead, it establishes a threshold: countries that join and maintain deforestation under agreed limits remain eligible for strong returns. If they exceed those limits, penalties sharply reduce their payouts.

Why this matters

The value lies not in the per-hectare figure but in predictable, large-scale budget flows tied to governance, monitoring and long-term certainty — shifting forest protection from scattered projects to national-level stewardship.

But the real test is still not the money. It’s who leads, who benefits, and how the system is shaped. This is where voices from the Global South — and inclusive-finance thinkers like Durreen Shahnaz — become essential.

A shift in where forest finance is designed

TFFF matters because it’s among the first major forest-finance instruments led from the Global South (Brazil, among others), not for the South. It shifts decision-making from micro-projects to national budgets, from donors dictating to recipients leading. It aligns forest protection with financial return, using governance and performance rather than charity.

Other efforts, such as the Forests & Climate Leaders’ Partnership, point in the same direction. To date, six countries — Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Colombia, Ghana, Papua New Guinea and the Republic of the Congo — have launched Country Packages for forests, climate and nature. Designed and led by participating national governments, the packages are grounded in national and local priorities, policies and legislation, ensuring they are country-owned and tailored to local contexts.

Durreen Shahnaz has long been a voice for inclusive finance and sustainable investment, arguing that capital must be accessible, accountable and aligned with local realities. Applied to forest finance, this means:

- If forests are part of a nature-based solution, then women, Indigenous communities and youth who steward those forests must be co-designers, not just beneficiaries.

- Inclusion is not a checkbox; it is foundational to performance, trust and legitimacy.

- Finance for nature must not replicate extractive models by dressing them up in green.

The TFFF — and any financial instrument designed to halt deforestation — must embed these principles, or it risks being status quo in green clothing.

Women from the Yanesha community play a vital role in stewarding forest landscapes, reflecting the importance of inclusive leadership in shaping fair and effective forest finance. Photo by CIFOR-ICRAF

Three pillars for meaningful, inclusive forest finance

- Equitable governance and benefit-sharing

- Forest nations must control design, governance and disbursement.

- Funds must flow to those at the frontlines: forest-adjacent communities, women’s groups, and Indigenous Peoples.

- Metrics must value gender contribution, community leadership and social outcomes – not just hectares saved.

- Policy alignment and local agency

- Finance without policy is weak: what matters is whether governments will and can enforce forest protection, repurpose subsidiesto make the forest sector competitive, and ensure that finance windows are inclusive.

- The Jakarta chorus reminding “we are only transitioning if not dictated by the North’s taxonomy” means: solutions must be built around local economic realities.

- The Global South must provide the policy answers — the thematic frameworks must be Southern-led.

- Scale, permanence and transformative design

- As Robert Nasi notes, the USD 4/ha figure is symbolic – the real lever is the structural guarantee, the scale (USD 125 billion target) and the risk/penalty mechanics.

- This must transition forest protection from voluntary projectism into core national economy and finance.

- The aim should be a scenario where a standing forest becomes more valuable than deforestation. That changes behaviour.

- Monitoring, transparency and accountability matter. If we rely just on “nice projects”, we fail.

What decades of evidence already show

At CIFOR-ICRAF, 45 years of applied science-based interventions show that equitable inclusion strengthens forest and landscape initiatives. When women and men have secure tenure rights, meaningful participation in decision-making, gender-responsive benefit-sharing and recognition of diverse forest knowledge systems, conservation outcomes are stronger and more sustainable. Our work on forest landscape restoration shows that when women lead planning and governance, local buy-in increases and ecological results improve.

TFFF could offer a powerful platform — if it delivers scale, local leadership, transparency and equity. Nature-based solutions must not simply be repackaged versions of old approaches but re-imagined models rooted in both green and orangeprinciples.

Simple questions, hard answers

TFFF represents a shift in who designs forest finance.

The test is straightforward.

In five years, will forest communities say this mechanism empowered them or bypassed them? Will women and Indigenous Peoples be co-designers or consultees? Will the Global South lead or merely participate?

These aren’t aspirational questions. They’re performance metrics.

The technology exists. The capital exists. What remains is the moral courage to build systems correctly with forest stewards at the centre, not the margins.

Because if we get this wrong again, we may not have the chance to try a third time.